Monitoring the disassociation of the EU from Russia

[ad_1]

Yves here. This post is clinically written, but nevertheless attempts to assess the impact of the EU’s effort to economically divorce Russia. This appears to be a fair effort, given resistance to being candid about rolling back sanctions. For example, it finds that Europe has no ready substitutes for 3/4 of Russia’s imports, mainly energy and “other critical and strategic raw materials.” Oh.

By Francesco Di Comite, Chief Economist team member, DG GROW (Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs) European Commission and Paolo Pasimeni, Senior Associate at the Brussels School of Governance – Vrije Universiteit Brussel; Deputy Chief Economist – DG Internal Market and Industry European Commission. Originally posted on VoxEU

The European economy was still reeling from the shock of the Covid-19 pandemic when the Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered further economic disruption, highlighting the importance of exposure to geopolitical risks and the vulnerability of international value chains. This column examines the exposures and dependencies of the EU economy at the time of the invasion and the massive adjustment that took place to disengage from Russia. Although the openness and flexibility of the EU economy allowed companies to reorganize their supply chains in a relatively short time, this adjustment may have structural impacts on the competitiveness of European industry.

The EU is one of the main players in world trade and one of the engines of the integration of international value chains. This has allowed the European economy to take advantage of the benefits of globalization, specialize in processes with high added value and increase its productive efficiency. However, in recent years a tension between efficiency and resilience has emerged. As the European economy was still reeling from the shock of the pandemic in early 2022, the Russian invasion of Ukraine triggered further economic disruption, highlighting the importance of exposure to geopolitical risks and the vulnerability of international value chains.

In this column, we look at these vulnerabilities and focus on the European economy’s effort to disassociate itself from Russia. In doing so, it complements a number of recent studies that have looked at the implications of post-invasion sanctions and disruptions in Russia (Demertzis et al. 2022) and around the world (Borin et al. 2022, Langot et al. 2022). , Attinasi et al.2022, Route 2022, OECD 2022, IMF 2022).

Disengaging from a structurally relevant trading partner requires multiple efforts. In a new article (Di Comite and Pasimeni 2023), we illustrate the ongoing large adjustment that the European economy is undergoing, identifying exposures and removing dependencies over the course of 2022. We analyze them from a risk assessment perspective, focusing on related dependencies and vulnerabilities, especially in imported commodities.

Russia’s importance as a trading partner of the EU was amplified by the concentration of its inputs in key supply chains. Commodities producing energy and other critical and strategic raw materials (CRSM; see European Commission 2020, 2023) have a low degree of substitution and a limited number of global suppliers. They account for more than three quarters of all EU imports from Russia. For most of these inputs, imports from Russia have declined significantly over the course of the year, indicating a reconfiguration of supply chains towards alternative sources.

On the Russian side, the EU was the main trading partner, providing a wide variety of investment goods and high-tech products. The sectoral structure of trade suggests that China represents a possible alternative to the EU for Russia, because it is a major exporter in those sectors where the EU was one of Russia’s main partners. These are usually the manufacture of machinery and equipment, computing and electronics, products made of metal and plastic, chemicals and textiles.

gross trade flows

At the time of the invasion, the EU was highly exposed to the import of Russian commodities, in particular fossil fuels and critical raw materials, but the data shows that it managed to gradually reduce this exposure throughout 2022. frequency data set based on customs data, we document a sudden and considerable reduction in EU exports to Russia just after the invasion. Imports adjusted more gradually due to the low degree of substitution of fossil fuels and critical raw materials. Furthermore, they became much more expensive in the weeks after the invasion.

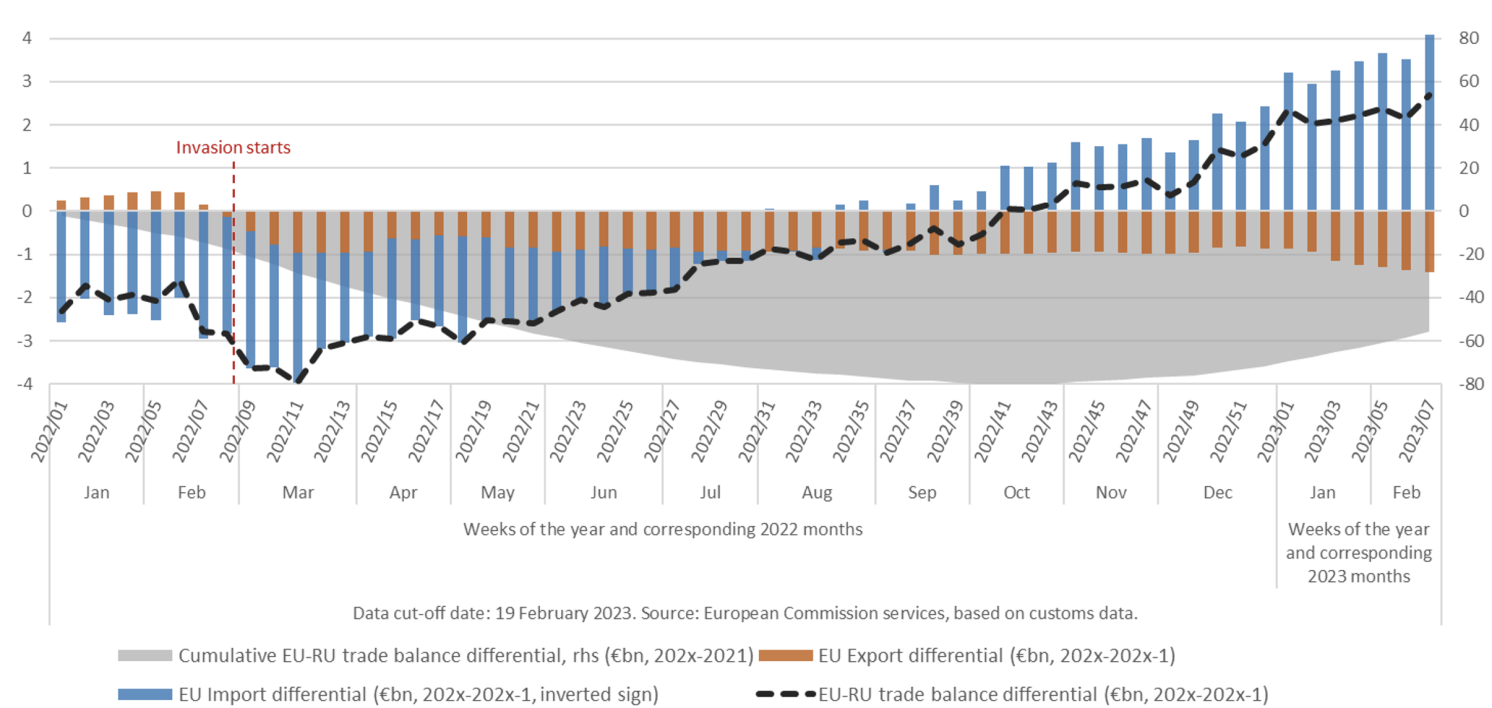

This has led the EU to run up an additional bilateral trade deficit with Russia of approximately EUR 67 billion in 2022, compared to the same period in 2021. This additional trade surplus for Russia corresponds to approximately 3.3% of its GDP and has probably been one of the factors behind the initial strengthening of your currency. However, with a sustained reduction in the volumes of imports of fossil fuels, by the end of 2022, the EU managed to stop, and even began to reverse, this accumulation of deficits vis-à-vis Russia.

Figure 1 Change in the EU-Russia trade balance with respect to 2021 (billions of euros, five-week moving average)

Strategic Dependencies

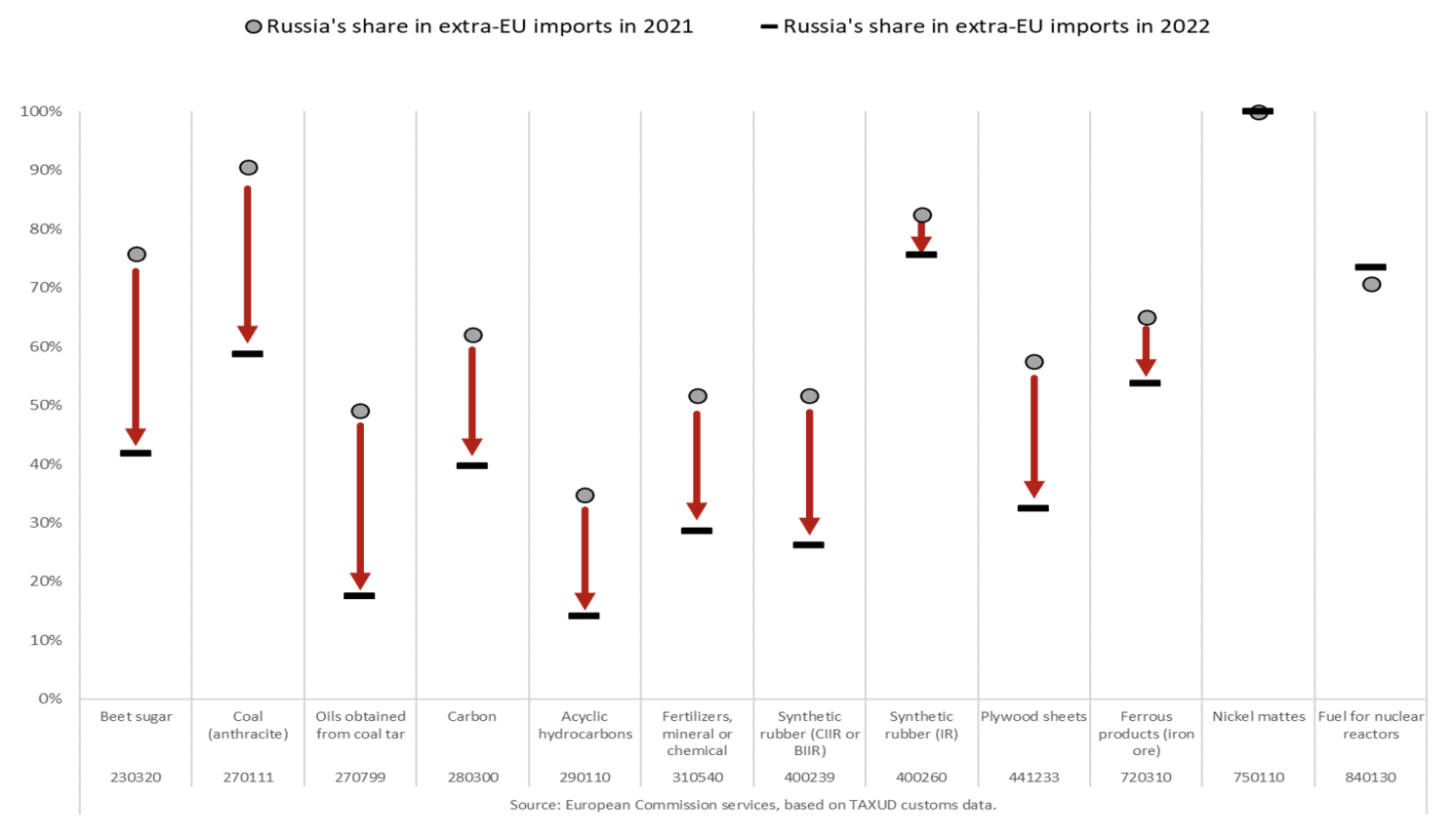

In recent years, the European Commission has proposed methodologies to identify “strategic dependencies” (products for which the EU is dependent on a highly concentrated set of foreign suppliers and has limited domestic production capacity (European Commission 2021, 2022)) and CSRM (Commodity Important). with high supply risk (European Commission, 2020, 2023). We were able to identify 12 strategic dependencies vis-à-vis Russia (of at least €100 million in imports) and 19 CRSMs. With some exceptions (nickel mattes and nuclear reactor fuels), imports of products for which the EU relied on Russia fell significantly over the course of 2022, on average by 20 percentage points in market shares. The supply of 11 of the 19 CRSMs decreased by 50% or more.

Figure 2 Russia’s EU Dependencies: Market Share Changes Between 2021 and 2022

Energy

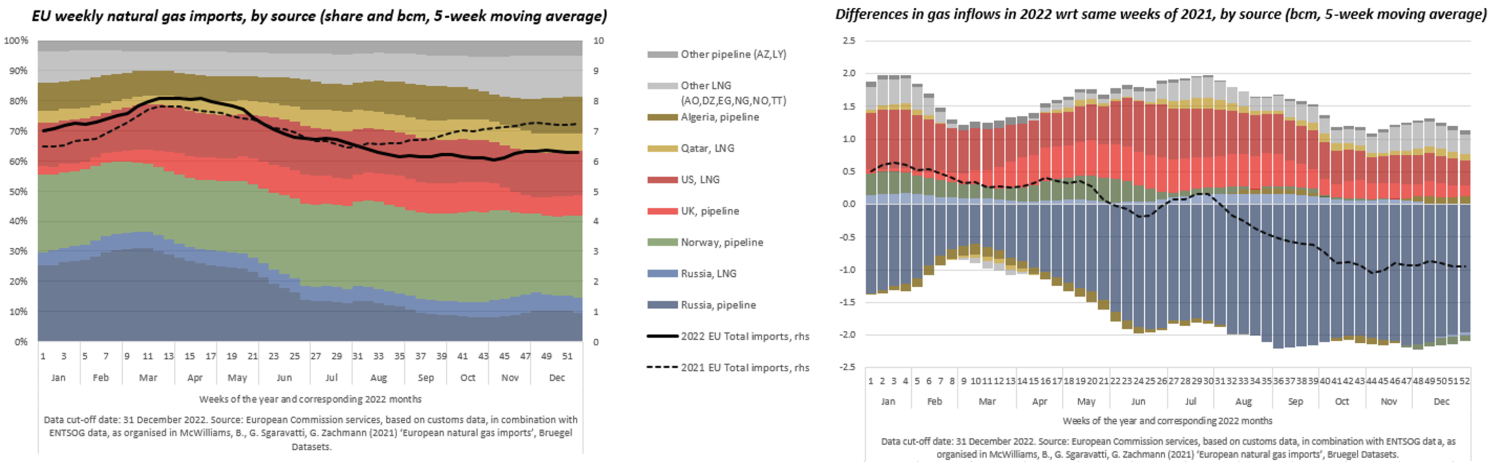

Energy products, and fossil fuels in particular, were key inputs for the EU economy from Russia (EUR 110 billion in 2021, 74% of total energy imports). Pipeline gas imports alone account for more than a third of all EU energy imports from Russia, and in February 2022 accounted for more than 30% of all EU gas inflows. Given that today gas is the marginal source used to balance the internal energy system, the evolution of its price determines the prices of the entire energy and electricity system in the EU.

The total volume of Russian pipeline gas imports fell by a third in 2022 compared to 2021, while the EU’s total gas imports in 2022 remained roughly at the same level, thanks to diversification towards alternative sources of liquefied natural gas (LNG): USA in particular. However, LNG import prices are 46% more expensive than pipeline gas import prices, with Russian LNG being the most expensive (Russian LNG import prices in the EU are 60% higher than average gas import prices) and US LNG % above average gas import prices). Therefore, a structural change from pipelines to LNG gas sources may imply for the European industry a considerable loss of competitiveness.

figure 3 Weekly flows of natural gas (gas pipelines and LNG) to the EU by source in 2022 and differentials 2022-2021

Conclusion

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has caused a permanent adjustment of the EU supply chains, with a progressive disengagement from Russia. On the one hand, the Russian economy is gradually losing one of its main sources of foreign income. The extent to which Russia can replace the EU with other trading partners remains an open question. On the other hand, the European economy is making a major adjustment in its supply chains, especially in key raw materials and energy products.

In general, the European economy demonstrated substantial resistance to the shock. Our analysis shows that the openness and flexibility of the EU economy allowed companies to reorganize their supply chains in a relatively short time. However, this adjustment may have structural impacts on the competitiveness of European industry, given the need to resort to second-rate supply chain configurations. If it persists, the relatively higher price of key inputs may lead to market share losses, particularly in key sectors for the green transition.

The unprecedented nature of this shock has prompted thinking in terms of resilience, business models, and supply chains that goes beyond short-term fixes. This crisis tested the resilience and adjustment capacity of the European economy. The challenge now is to ensure the sustainability and competitiveness of emerging supply chain configurations.

See original post for references

[ad_2]